Overview

Our company is in the process of switching from one PSA system to another in the next few weeks. This change involves a lot of work and adjustments with how we organize and structure ourselves internally. We currently have a bunch of projects, and the problem is that our old PSA system mostly dealt with “ticket”-based entries, so there wasn’t a dedicated way to store our progress on all these projects.

Thankfully, our new PSA system now draws a line between projects and ticket-related work. I’m still adjusting to how it works, but I’ve encountered one major issue: migrating all the notes from our previous PSA to the new one is exceptionally time-consuming because there’s no export/import feature available. I wanted to find a solution that would make it easy for our team to export and import ticket notes in our new PSA. Another problem I faced is that our old PSA used CSS formatting for ticket information rather than HTML. Simply copying and pasting the ticket notes would result in a messy, unhelpful mishmash of information.

So how did I combat this? The very first thing that I always love to do when it comes to automating the web is to create a Chrome extension. Some may argue that there are better ways but this is by far the quickest way to prototype any sort of web-based tools.

Manifesting the Manifest

Just like in all my projects, I begin by setting up a root directory. In the case of this project, I’ve named it “NoteExporter.” Many of my tools involve various components working together, and I find it helpful to organize them into separate subfolders. While I don’t anticipate needing any additional components like a Python script for this project, having a neat root directory allows me to change things easily in the future. That is why I created a new directory specifically for storing the files related to the Chrome extension.

Within that new folder, this is where all the Chrome related stuff will go. Every Chrome extension must have a “manifest.json”. The manifest file serves as a configuration file that provides information about the extension to the Chrome browser. It defines the extension’s structure, functionality, and permissions. Here is what I consider the “essentials” of every manifest file:

1 | // NoteExtractor/note-extractor/manifest.json |

Manifest Version: This specifies the version of the Chrome extension manifest format being used. I wanted to use the latest format so version three would work best for this case.

Name: The name field specifies the name of the extension. This is a human-readable name that would be displayed on the Chrome Web Store if I decided to publish it.

Version: This is a version that follows the developers own versioning format. It is used to manage updates and ensures users have the latest version. I recommend looking into versioning best practices if you are developing a large Chrome extension, but for me, I used my typical “0.1.0”. There’s tools out there that will also help you integrate your versioning with a repository platform such as GitHub.

Action: This defines the behavior of the extension by “linking” scripts or pages that run in the background and control the extension’s functionality.

Description: This describes the purpose of the extension.

Icons: These are the icons that will be used when users find the extension in the web store or browses their installed extensions or accesses the extension on the top right of the window.

Author: I wonder what would go here. I must consult the official documentation!

Gathering Request Data

Once I’ve got my manifest file sorted, I’m ready to dive into my plan. The very first thing I need to get my hands on for my extension to actually do its job is the PSA ticket notes. Now, there are a couple of ways that I could of fished out this info, but a saying I always keep in mind is, “garbage in, garbage out.” With that being said, the first way is a not so good way. By messing around with the website’s HTML code, you will notice most stuff on a website has a class or an ID slapped on by the developer who made it. So, for example, if all my ticket notes belong in a list with the class name “psa-notes,” I can easily grab them using JavaScript:

1 | <ol class="psa-notes"> |

1 | Output: |

This approach for collecting notes is effective when the information we require has identifiable markers, like a class or ID. However, it can be challenging when dealing with a well-structured HTML format like our current PSA system, as it can make the task more difficult due to the need for precise conditions.

Now, there is a second method I would like to explore for extracting ticket information. It’s obvious that the ticket notes aren’t statically inserted on the webpage but are dynamically loaded when the page is accessed through an API call. This means that somewhere within the website’s structure, there is raw ticket note data. My script needs to access this data somehow.

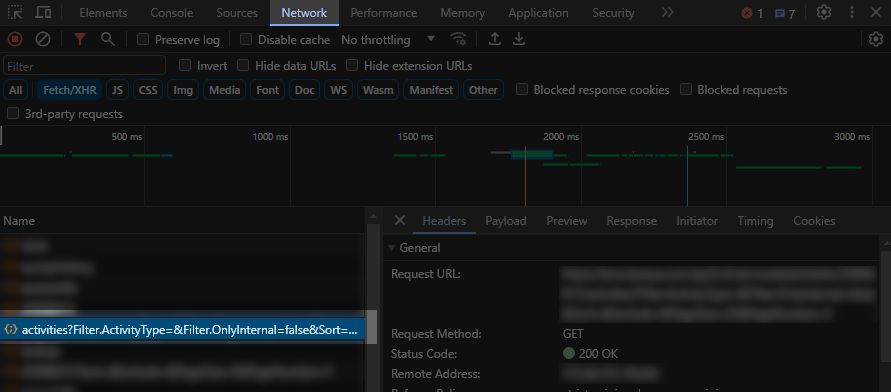

When a website requires information from the server, such as ticket notes, it creates a web request to the server, which responds with the requested data. This can all be monitored using the Chrome DevTools, accessible under the “Network” tab at the top of the browser. While there might be a substantial number of requests, it didn’t take long for me to pinpoint the specific one I needed for this task.

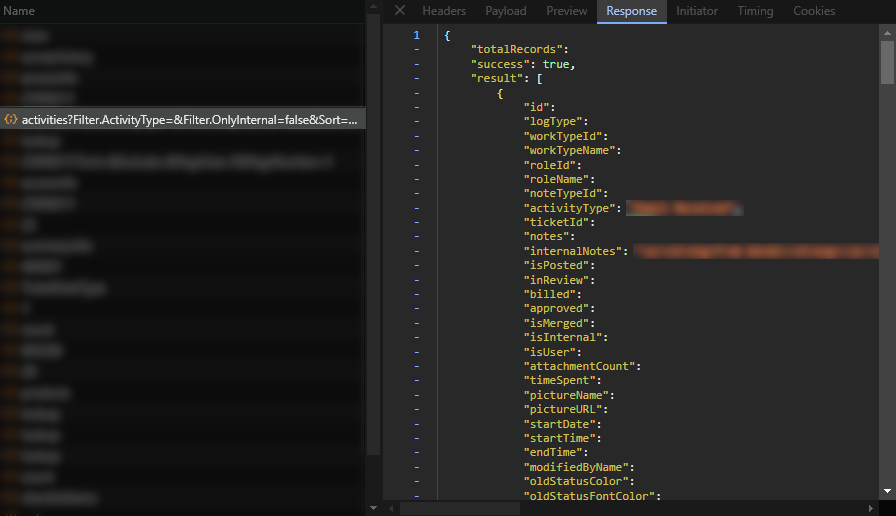

The GET request activities?Filter.ActivityType=&Filter.OnlyInternal=false&Sort=&Exclude&PageSize=25&PageNumber=1 contained a JSON object from the server with a beautifully formatted list of all the JSON data involving the ticket notes.

This essentially means that I have found the web request that I need to call every single time I want to export my ticket notes. I originally was trying to access the already existing JSON response but I couldn’t figure out how to get it to work so I just decided I will call it myself. I figured it wouldn’t be too hard until I missed some key details that would have prevented me a headache if I had just paid attention.

Typically, when you want to call the web request yourself, you can right click the request and copy the request in different formats. For a basic JavaScript request, I had picked “Fetch”. The copied request looks a little like this:

1 | fetch("https://abc.example.com/api/desk/tickets/<ticket ID>/activities?Filter.ActivityType=&Filter.OnlyInternal=false&Sort=&Exclude=&PageSize=25&PageNumber=1", { |

There is a couple of things I want to point out here. The first is that I had changed the API link to something generic enough so people can’t just pinpoint exactly which PSA system I used. The second thing is within the API link, you will notice a <ticket ID> field. This is replaced in code by the ticket we want to get the notes from. Each ticket that is created is assigned a specific set of numbers and those numbers are used to uniquely identify tickets. The third thing I want to point out is the "authorization": "Bearer <auth code>" field. This is required because only authorized users can access ticket data. The authentication code is usually stored within the browsers cookies, which you will see later.

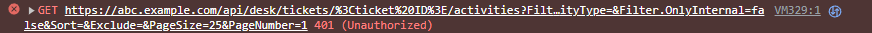

When pasting this request in the DevTools console and sending it through, I actually got an error.

This really confused me because I checked the other requests and nothing was changing between them. I had initially thought the developers had put in some sort of API key generator that would generate a valid key every time the API is called to prevent someone like me from simply copying and pasting the request, but there was no API key. I went through an hours worth of troubleshooting and at one point I decided to resend the request and it went through. Every request from there on out had completed successfully. I still don’t know what I did differently at that point in time but I am glad it was fixed. I was seriously looking into spending hours deobfuscating JavaScript code.

Creating the Prototype Extension

It was now time to begin programming this extension. For reference, this is what my file structure looked like at this stage:

1 | NoteExtractor (root)/ # Root folder |

Now I want my extension to create a button somewhere on the PSA site that looks like it belongs there. When that button is pressed, it will take all the ticket notes, format them into something that can be pasted, and then write it to the clipboard. In order to manipulate the content within the PSA ticket page, I needed to create a content.js script inside note-extractor/. This JavaScript file will serve as the main gut of the entire extension.

However, creating the the content.js file isn’t all. I needed to let Chrome know that it exists through the manifest.json file as well as grant it permission ONLY on ticket pages.

1 | // NoteExtractor/note-extractor/manifest.json |

This essentially instructs Chrome to load the code from the content.js file and add it to the end of pages matching the pattern abc.example.com/desk/mytickets/* or abc.example.com/desk/tickets/*. The asterisk acts as a wildcard character, which says “anything can go here”. The ticket number at the end of the URL allows our script to load only on the desired page.

One thing I do want to point out is that I originally did not include the first link in the "content_scripts" field. This oversight caused me a ton of issues because I didn’t realize tickets that are assigned to me and that are not assigned to me are under two different paths.

Anyways, in the content.js script, I opted for a straightforward approach to start prototyping. I introduced a basic export button designed to trigger a Hello, World!alert. In order to find out where I can put this button, I used the DevTools to find an element I can use as an anchor point on the website. For the time being, I used a specific element that was conveniently identified by the class .psa-searchable-items-header.

Once my script identifies this element, it proceeds to create a button. It then assigns the desired text to the button. When this button is clicked, it initiates an alert message to notify the user.

1 | // NoteExtractor/note-extractor/content.js |

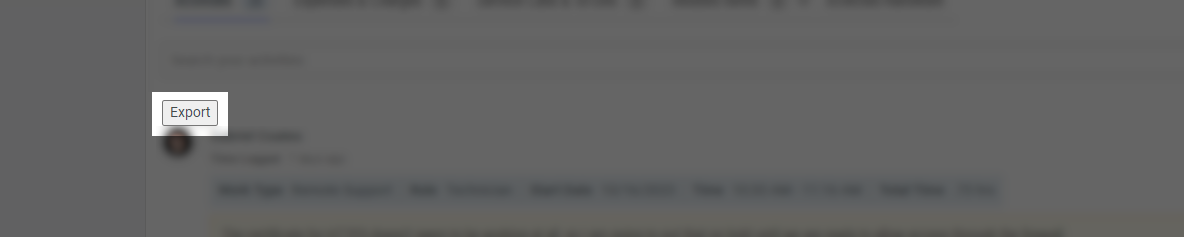

I imported my extensions folder into Chrome and refreshed the ticket page. Thankfully, I am greeted with my button right above the ticket notes and everything seems to have worked.

Fetching and Accessing the Data

The final phase has started. What I aim for my script to achieve is to call the GET request from earlier and utilize the JSON response to format the notes in a user-friendly manner. Once that is complete, as I explained earlier, it will copy the formatted notes to the clipboard, enabling anyone to easily paste them into the new PSA system.

At first I had just thought about keeping it simple and triggering the GET request every single time the button is pressed, but I decided not to do that for several reasons. I didn’t want alert any API monitoring systems, it was inefficient, and the ticket notes don’t update until the user refreshes the page anyways. So rather than triggering the GET request when the button is clicked, my plan was to execute it as soon as my script loads. It will then store the request information in a variable, ready for formatting and access when the button is clicked.

getAuthCookie()

The very first function I had defined in my content.js script after deleting everything was a simple method that retrieved my authentication cookie. Remember, this is needed in every API call in order to authenticate myself with the server.

1 | function getAuthCookie() { |

- The function starts by collecting all the cookies that the website has stored.

- Among all the cookies, I am only interested in one specific cookie called “PSAAuthToken=”.

- The function then goes through the list of cookies one by one. For each cookie, it removes any extra spaces to prepare it for copying.

- If the cookie that is selected on the current iteration starts with “PSAAuthToken=” it means it has found the correct one.

- When the function gets the right cookie, it grabs the whole cookie. However, it doesn’t need to include the name “PSAAuthToken” in the key. To fix this, I used the length of the cookie’s name and skip that many characters to get just the key.

So, in the end, it extract the authentication code that proves the users identity without including the unnecessary “PSAAuthToken=” part.

extractTicketLinkData()

The GET request requires both the API link and the referrer link in order for the GET request to function properly. This includes grabbing the ticket ID and the proper path name depending on if the current user has been assigned the ticket or not.

1 | function extractTicketLinkData() { |

- The function begins by determining the current tab’s URL.

- It then utilizes a regular expression to search the URL and extract all numerical values from the URL (which happens to be the ticket ID).

- The function checks the type of ticket whether it be assigned to the current user or not.

- Finally, it creates an array that includes the extracted ticket ID and the desired referrer path.

getTicketNotes()

With the functions from earlier, my extension is now ready to grab the ticket notes in JSON format by calling the GET request.

1 | function getTicketNotes() { |

- This method first gathers the necessary information from the other methods.

- Then it crafts a web request using the ticket path data, ticket ID, and authentication token.

- Finally, it stores the returned data from the API call in its own variable to be access later.

formatTicketNotes()

My extension is finally able to make a successful GET request and retrieve all the ticket notes in JSON format. This is some good news as I can now begin formatting the text into what would be ideal when importing.

I do want you to pay attention to how it gets the individual notes and email notes. Because email formatting works the way that it works, when copying from the ticket notes, it tends to include left over HTML elements which makes the notes seem cluttered. That is why on every entry I execute the “stripHTML” method.

1 | function formatTicketNotes(jsonData) { |

- The method first starts by creating an empty string variable to store the formatted text.

- It then iterates through the JSON file. The notes are located within the “result” section of the JSON data.

- For each individual note, the function extracts key pieces of information such as the author, timestamp, and the content of the note.

- An if statement is then used to identify what would be the best formatting to apply to the current ticket.

- Within the if statement, the function will gradually build upon the formatted text variable by adding the relevant information in the desired format.

- Once all notes are processed, the function returns the final formatted text to be used.

stripHTML()

This function essentially performs the following steps: it extracts the presumed HTML content from the notes, establishes a root element, incorporates the HTML content from the email into this root element, and ultimately provides the inner text, excluding any HTML elements.

1 | function stripHTML(html) { |

addExportButton()

This function is almost the same as the prototype version. The reason why it’s different is because I am finally applying some styling to the button to make it fit in. I also changed the positioning of the element within the page. Now, we need to provide users with a convenient way to access the JSON data. As mentioned earlier, the goal is to implement a button that can copy the well-structured data to the user’s clipboard without repeatedly sending GET requests.

I started by selecting a parent element to which the button will be added. In this scenario, the side navigation bar serves as the parent element. I create a list component that will be inserted into the navigation bar’s list. I will then add text to the button and apply some styling to ensure it blends seamlessly with the user interface. Finally, I set up an event listener that triggers when the button is clicked.

When the button is clicked, it initiates the execution of a ‘copyToClipboard’ method. This method takes the formatted text and copies it to the clipboard, making it readily accessible to the user.

1 | function addExportButton(exportElement) { |

copyToClipboard()

This is a really simple function and simply uses the navigator library to write the formatted text to the clipboard and alert the user when it is done.

1 | function copyToClipboard(text) { |

initialize()

The brains of the whole operation. This function is a bit more complex compared to the others. I encountered some challenges while trying to find a solution, but this one appears to work quite well. The first issue I faced was related to having multiple tickets open in the same window, but only one could be selected at a time. Whenever you switched between these open tickets, the page underwent a rerender (not a full refresh), and the URL was updated. I’ll provide more details shortly on how I resolved this. The second problem I encountered was the difficulty of triggering events to let my extension know when the page had finished loading. I had to implement a sort of heartbeat method. I created a variable to keep track of the number of attempts, ensuring that we didn’t overwhelm the page with commands while it was loading. If there was no root element initially to attach the button to, the script will had performed a periodic scan for the button on each iteration. If nothing was found, it waited for 2 seconds. If this situation occurred 10 times in a row, it stopped, and the user had to reload the page. However, if the root element was found for our export button, we simply added it to that root element.

1 | async function initialize() { |

Fixing the Ticket Swapping Problem

Now, let’s dive into the specific steps I took to resolve the ticket swapping issue. As mentioned earlier, when you switch between open tickets within the same window, the page refreshes, and the link gets updated. This behavior prevents the “initialize” function from running again, which makes the extension useless. In response, I decided to employ the “chrome on message” method.

To implement this solution, I introduced a service worker to operate in the background and monitor the tabs. The first step in this process is adding it to your manifest file:

1 | // NoteExtractor/note-extractor/manifest.json |

This lets Chrome know I also have a background service worker. I simply add a listener to the file:

1 | // NoteExtractor/note-extractor/background.js |

This function runs whenever a tab gets updated, including changes to the URL. To avoid sending a message to every open tab, I made sure that the URL of the current tab matches either https://abc.example.com/desk/tickets/ or https://abc.example.com/desk/mytickets/. When there’s a match, I send a “urlChanged” message to that specific tab, where my content.js script is waiting to receive it.

After all of these preparations, I can easily navigate to any ticket and click the export button. This action will copy all the properly formatted contents to my clipboard, allowing me to paste them into our new PSA system, specifically within our projects.

Conclusion

Was this over engineered? Probably. Could it have been done more quickly by manually moving ticket notes? I actually had a Python script that managed the task in just about 10 minutes, so yeah. Is there a more efficient approach to tackle this? Most probably. But was it worth it? Definitely. I hardly tinker with non-public APIs, so this project was a valuable learning experience.

One future change I have in mind, apart from implementing some user-friendly updates, is a method to track the current ticket note JSON data. Even if the “export” button doesn’t trigger the GET request, every time we switch between open tickets, it still initiates that request. I’ve explored how the PSA system handles this, and it fetches the ticket notes for all open tickets at once, leaving additional requests until the page is refreshed. I want to have similar efficiency, reducing the API calls to just one per page refresh.

That pretty much sums up my findings in this project. If you’re interested in reviewing the source code, you can find it on my GitHub page. And if you’d like to see the final, neatly formatted notes, you can see them below:

1 | Activity Type: Status Changed |